Gerry Coker: Making His Marque

1956 Austin-Healey 100M Le Mans. (Courtesy of RM Sothebys)

Imagine being asked to design a car having never done so. Then, imagine the car you come up with is the Austin-Healey 100.

THE MORNING CALL | Aug. 19, 1995

Larry’s note: This is the first automotive story that I wrote. I was a full-time cartoonist and graphic artist at the time.

Donald Healey was nervous.

His small British car company was about to introduce a prototype of a new sports car, and now that he had arrived at The Turin (Italy) Auto Show, he sent for the car’s designer, Gerry Coker.

After looking at the various models around the show, Healey asked Coker if he was still sure the car was all right. “What was I going to say?” Coker asked. “Scrap it? Never, and I was nervous because I had never designed a car body.”

Of course, when the first car you’ve designed is the Austin-Healey 100/4, it’s safe to say you have little to worry about.

Coker, desiger of the Austin Healey 100/4, 100/6 and the “bug-eye” Sprite, is the guest of honor this weekend at the Austin-Healey Sports and Toruing Club Encounter at the Days Inn at Routes 309 and 22 in South Whitehall Township. Events include a car show, Concours d’Elegance and a rally. More than 100 cars from as far away as Quebec and the Carolinas. They’re here to celebrate the two-seaters and the man who designed them.

Despite 25 years at Ford and three years at Chrysler, it is Coker’s association with Healey’s car company that’s brought him the most notice, After completing a five-year apprenticeship with the Rootes group (later Chrysler U.K.), Coker met an acquaintance of Healey, who needed an engineer for his car company. Soon, Coker was at work designing components for the established designs that Healey was producing.

But that soon changed.

“After coming back from America one time, he came back and said what he wanted. He’d like to have a car that fit betwen the MG and the Jaguar.”

Healey was a pretty small operation, and Coker had a relatively free hand.

“There were three of us in the drawing office,” Coked recalled, “a boy learning to be draftsman, a chassis designer and me. I was very into Italian styling; I thought they had the greatest stylists. So he was going to get an Italian car. Healey didn’t know what he wanted, but I knew what I liked.”

The result was the 100/4, a graceful two-seater bult around an Austin 4-Cylinder engine similar to the one used in London taxi cabs. The windshield is deigned to fold, enhancing aerodynamics when the car is raced. The 100/4 is relatively simple to help keep its weight and cost down. It lacks such features s roll-up side windows. But f you find that odd, you don’t understand the appeal of the car. Although later versions were offered with 6-cylinder engines, roll-up windows and longer wheelbases, Coker’ contributions were those that please the eye. A new 100 was dsigned, but never saw production.

Before leaving Healey, Coker also designed the Sprite, populalrly known as the bug-eye.

1959 Austin-Healey Sprite (Courtesy of RM Sothebys)

“Don thought there was a market for a sports car that a chap could keep in hsi shed,” Coker said.

As a result, the car lacks a rear decklid, the whole front ed tilts forward and there are no side windows or door locks, all in an effort to keep it simple and cheap. Originally, the car was designed with retractable headlight, but they were eliminated in an effort to shave costs.

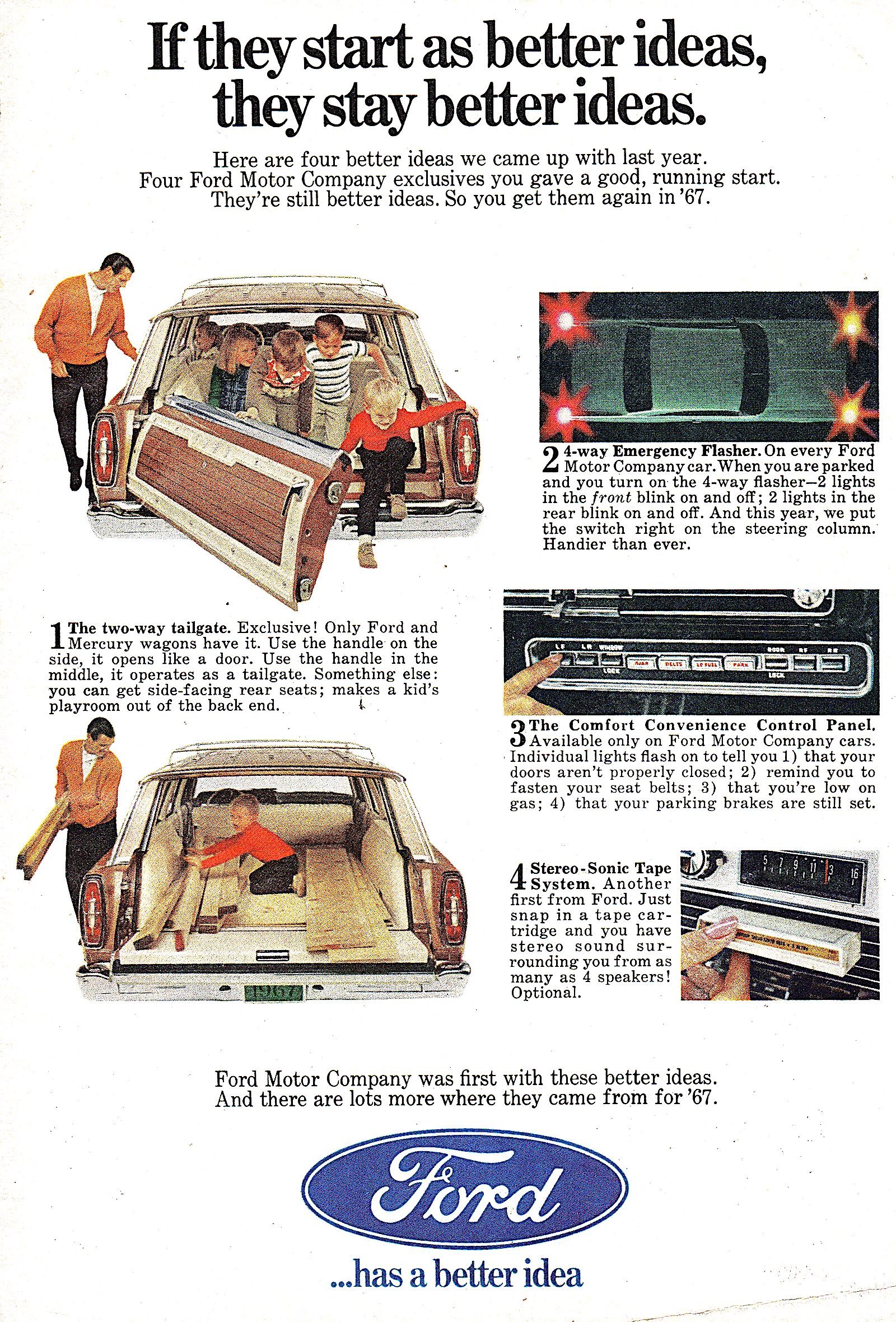

By the time the Sprite saw production, Coker had left for America, first working at Chrysler, then at Ford. There, his dutues included working with folding seat and other interior packaging problems. Ultimately, he deigns the familair dual-action tailgate.

Although it’s been a while since Coker designed a car, he still relishes the job he did and the excitement that surrounded it.

“Don got it from a friend of his that Standard (Car Co.) was coming out with a new sports car the same day as ours. As it happened, the head of Standard Cars, Sir John Black, looked at their car, which was the TR-1, and took all his men across to ours and said to his men, ‘I want something like that.”

As Coker says, “It was the best thing I’ve ever done.”

Coker’s talents were wasted at Ford, where his only legacy is the dual-action tailgate.